No more arresting emblems of the modern culture of nationalism exist than the cenotaphs and tombs of Unknown Soldiers

Halbwachs spoke of the non-linear development of collective memory, when a sense of reality is inseparable from real life. And social groups and their interests shape the perception of the past. Hobsbawm explained the orientation of collective memory to the present because society strives for historical continuity. He suggested that political and social changes occur through the “invention” of new rituals and symbols. These symbols can be reused to legitimize government political and military actions. Putin’s rise to power ushered in a brutal era of politicization and memory manipulation. In his inaugural speech on May 7, 2000, he stated:

...there is the concentration of our national memory in the Kremlin. Here, within it’s walls, the history of our country was made, and we have no right to be Ivans who do not remember kinship. We must not forget anything, and we must know our history. Know it as it was, learn from it. We should remember those who created the Russian state, defended its dignity, made it a great, powerful, mighty state. We will preserve this memory and maintain this connection of times… I consider it my sacred duty to unite the people of Russia, to gather citizens together around clear goals and objectives. And to remember during every day of serving the fatherland: we have one homeland, one people. You and I have one common future ahead.

His rhetoric was built around the inextricable link between modern Russia and its “thousand-year” history, thereby legitimizing the Putin regime as the legitimate historical successor to both the Russian Empire and the USSR. The “unity” of citizens was the national idea, which was formed on widely recognizable, positively, and unambiguously perceived symbols and rituals. According to the Levada Center survey about World War II in 2003, 84% of Russian families had or were participants in the Great Patriotic War, and 80-85% of citizens celebrated Victory Day. In a 2006 survey, “What date should be celebrated as the main public holiday?” 57% answered—May 9th. In the complex and ambiguous context of the events of the last century and the context of Yeltsin’s electoral policy of alienation from the Soviet past, Victory Day and the Great Patriotic War became the main and only possible symbols of the unification of society, from which the Putin's regime formed the national idea.

The search for national identity

The collapse of the USSR gave rise to the search for a national identity for the newly formed Russia. On July 30, 1996, in issue No. 142 of the Rossiyskaya Gazeta, under the heading “Who are we? Where are we going?” there was a small announcement on the main page about the competition called “The Idea of Russia”. Everyone who “believed in a reviving Russia, talent, diligence, and patriotism of Russians” and who was ready to present a nationwide unifying idea of Russia in 5-7 pages was invited to participate. They proposed to send such ideas to the editorial office of the newspaper with the note “The idea for Russia”. The newspaper promised to reward the author of the best idea with ten million rubles. This competition was published in the official newspaper of the Government of the Russian Federation precisely 27 days after Yeltsin’s victory in the 1996 presidential election, which was characterized by a manipulative informational campaign in his support.

The collapse of the USSR and subsequent events did not launch a radical rethinking of Soviet history, a redefinition of morality and social relations. They did not lead to lustration on the territory of Russia. The myths formed by the Soviet past did not disappear completely. They were fixed in a hybrid form, with the rejection of some historical aspects and the consolidation of others. The leaders of the Communist Party continued to use the slogan “For our Soviet Motherland” while at the same time declaring that they were not “the party of Trotsky and Beria, Vlasov and Yakovlev, Gorbachev and Yeltsin”. The democrats, having initially abandoned patriotic myth-making due to associations with communist propaganda, failed to build a new narrative around the events of the 1991 putsch and “freedom”. In the end, when they realized they were about to lose their power, they partially returned to celebrating the positive aspects of the Soviet past. Political actors, pursuing their goals, mobilized the familiar Soviet collective memory, seeking to unite citizens around the symbolism of the past.

Yeltsin and the Russian government attempted to mythologize new potentially popular historical symbols that could shape Russian identity. For example, one of the significant events was the putsch in August 1991 and the victory over the putschists. In the beginning, the myth of the “overthrowing of the junta” revolved around honoring three people who died during the coup. A memorial stone was installed in their honor, the citizens who participated in the opposition were awarded medals, and the square in front of the White House was renamed Freedom Square. However, the celebration of the victory over the putschists turned into an indistinct “Day of the Russian flag”. The Day of Independence of Russia was timed to coincide with the proclamation of state sovereignty by the RSFSR on June 12th, 1990. It raised questions in the wording since it was unclear from whom Russia wanted to be independent, being the “main” Soviet republic. The adoption of the constitution of the Russian Federation on December 12th, 1993, also did not become an official public holiday due to the lack of parliamentary support. None of the new holidays were popular among the citizens, and none of the citizens participated in them.

In parallel with the failures in the new mythology, the celebration of the October Revolution remained the official holiday of the communists, and Victory Day was an important day for all citizens. While the democrats completely denied the holiday around the revolution, May 9 was not so unambiguous and required the adaptation of Soviet patriotic myths to the realities of democratic Russia. The critical narrative of the democrats revolved around the fact that the victory over fascism was a deed of the people not because of, but despite Stalin and the party. On May 9, 1992, instead of a military parade on Red Square, there was a procession of veterans not only from the former Soviet republics but also from the United States, where former prisoners of concentration camps also took part. The Communists accused the Democrats of neglecting the holiday, that the German band marched with the veterans, and that they downplayed the national victory and killed the spirit of patriotism. The celebration of Victory Day has become a between communists and democrats.

By 1995, the Yeltsin government realized the holiday’s impact on patriotism, especially in an unstable economy. The celebration returned to Red Square, and the parade of military equipment was held on Poklonnaya Hill. In addition, the rituals of the parade remained the same as in the USSR: the leader is on top of the mausoleum, and the Minister of Defense is driving around the soldiers in a car while they shout “Hurrah.” For the first time, the Soviet and Russian flags were officially placed together. On May 19, 1995, Yeltsin signed the law “On Perpetuating the Victory of the Soviet People in the Great Patriotic War,” in which Victory Day was declared a national holiday and a non-working day with an annual military parade. Along with this, responsibility for the preservation of monuments and memorial structures was introduced. There were several resolutions as well: fight against fascism on the territory of the Russian Federation, bans on the public identification of the USSR with Nazi Germany, and on the denial of the decisive role of the Soviet people in winning the war. A partial return to the Soviet rituals of celebrating May 9 and the consolidation of the special status of the Great Patriotic War at the legislative level marked the beginning of the institutionalization of the collective memory of this historical event.

Institutionalization of the collective memory of the Great Patriotic War

Although Putin officially voiced patriotism as a national idea only in 2016, the institutionalization of historical memory and patriotic education began in 2001. Five state programs for the Patriotic education of Russian citizens—2001–2005 (funding 177.95 million rubles), 2006–2010 (funding 497.8 million rubles), 2011–2015 (funding 777.2 million rubles), 2016–2020 (funding 1718.6915 million rubles), 2021–2025 (funding amount not published)—were approved by law. The program affected different age and social groups and the family structure as the primary unit of society. Political and social goals were aimed at consolidating the society around patriotic ideas, strengthening the state’s image among the population, and increasing the educational impact of Russian culture, art, and education on the formation of patriotism. Raising the prestige of the military and public service, the construction of people loyal to their motherland and ready to fulfill their duty to protect its interestswas brought into a separate category.

The government created and supported projects that were related to patriotic education and military commemoration: Victory organizing committee for holding events related to the Second World War; the movement of Russia to perpetuate the memory of those who died defending the fatherland with the search for bodies and their burial; the patriotic campaign “We Remember” for the high schoolers and the college students; the opening of the historical park “Russia—My History” at VDNKh; support for military museums and expositions; holding military festivals for children; celebrating anniversaries of military events and its dates; establishing monuments and memorial signs; publishing popular science historical journals; funding historical patriotic cinema, murals, and themed trains.

In parallel with the support and funding program, memory institutions and laws that control history were created: 2002—the Russian Center for Civil and Patriotic Education of Children and Youth; 2004—the Historical Perspective Foundation; 2008—the Historical Memory Foundation and the Federal Agency for Youth Affairs; 2009—Presidential decree on the Commission under the President of the Russian Federation to counter attempts to falsify history to the detriment of Russia’s interests; 2012—Presidential decree on holding the Year of Russian History, the Russian Historical Society and the Russian Military Historical Society (with the opening of regional branches throughout Russia); 2015—Yunarmiya for children from 8 to 18 years old. The focus on the events of the Second World War, although it was not the only one, was of key importance for the formation of national myths.

Formation of myths

Hutchinson spoke of four mechanisms through which wars shape a nation: wars are the material of myths, whose unique narratives give meaning to society; they build a we-they stereotype from which collective self-determination develops; they form social rituals that develop a sense of community; finally, the results of the war may induce public policy, and both individuals and society as a whole, to introduce these rituals and symbols into daily life. He claims that “war can give rise to a set of historical myths that are fixed in the minds of the population so that they become the basis for explaining and evaluating events”.

Assuming that collective memory is non-linear and modern reality forms the perception of the past (Halbwachs), we can assume that the national myth (in this case, the myth of the Second World War) is also the object of constant reconstruction, changes. The focus here is on the “positive” aspects of the historical event while ignoring the “controversial” points. Putin, in his speeches, developed a moral argument where Russia acts as a missioner, the liberator of Europe from fascism. By this, he legitimized the discourse of the victim, whose suffering requires, if not compensation, but unconditional respect:

… it is a sacred duty to respect the memory of the fathers buried in their native land and on the battlefields of Europe. Our people gave everything to victory.

“Russia is consistently pursuing a policy of strengthening security in the world. And we have a great moral right to fundamentally and persistently defend our positions because it was our country that took the hit of Nazism, met it with heroic resistance, went through the most difficult trials, determined the very outcome of that war, crushed the enemy and brought liberation to the people of the whole world”.

The constant reference in speeches to virtue, service to the state, and the homeland raises to a cult those who died in the battles for the country. The death and ongoing commemoration of heroes bind subsequent generations with blood. They died for the future of the unborn and are immortal because the memory of this deed will live forever. This automatically obliges the new generations for which they died to repeat the fate of their ancestors to fulfill their duty to them. Patriotism and nationalism merge in the same circle with death and its repetition:

“Today, every boy in Russia knows about Stalingrad, knows about the Battle of Kursk. In fact, every family has its heroes. Their own heroes of that cruel war. Both this knowledge and this memory are immortal. This means that the greatness of the Motherland is also immortal. The pride of the people and Russian patriotism are immortal. And therefore, no force can defeat Russian weapons and break the army <…> Your fate and your acts of bravery are the best school of life. An example for those who raise our new strong state”.

“When the question of protecting our native land arose, all of our people rose. Where did his enormous spiritual power come from, his willingness to sacrifice oneself? All this arose out of sincere, heartfelt love for one’s country. These feelings of patriotism are passed on from generation to generation, and you understand this especially keenly when Victory Day in the Great Patriotic War, May 9, comes: it’s as if you hear how the hearts of all people beat in unison. Such a powerful unity of veterans, their children, grandchildren, and even their great-grandchildren is unprecedented”.

This rhetoric, in conjunction with a large-scale patriotic educational program and media propaganda, has formed two myths. The first turned outward and followed primarily geopolitical goals: “Russia is the liberator of the world and Europe”. The second is directed at its citizens: “Previous generations died for their homeland and therefore are immortal. Future generations must repeat their fate.”

Fixing rituals and symbols

Rituals and symbols, already known or newly invented, embody myths in performative bodily actions, and by following them, participants unite. Rituals are tied to certain calendar dates; their effect is based on the constant repetition of the same codes. The state is the structure that determines the national holidays and the number of non-working days in the calendar so that citizens can find time to practice the rituals of commemoration.

The most recognizable state ritual is the victory parade on Red Square, which follows the same scenario every year. In 2008, it was decided to resume the display of military equipment, which marked a direct association with the Soviet tradition and a demonstration of the ‘power’ of modern Russia. The parade has always remained closed for the citizens and was broadcast on the main state channel. The official part of the celebration has always been mixed with personal, as a family celebration. It was customary in my family to watch the parade on TV, then go beautifully dressed to lay flowers at a small stele with a red star and the inscription “No one is forgotten—nothing is forgotten,” to tell veterans heartfelt military poems about young guys and girls who went to the front and did not return. The veterans, in response, shared their memories and let us touch their medals. Military hits always played loudly, and the children bragged to each other about whose grandfather had died and who had returned. All this ended with the rituals of sharing food somewhere in nature, where people often consumed alcohol as a ritual to remember those who died in the war.

New symbols were applied, such as the St. George ribbon and the “Immortal Regiment”. Introduced in 2005 by journalists from the state news agency RIA Novosti, the St. George Ribbon action is now considered inseparable from the May 9 holiday and is a symbol of victory. A 2007 poll shows that 76% have a positive attitude towards the symbol and perceive it as “pride for the country”, “preservation of memory,” “respect for veterans,” and “sacred celebration of victory.” This symbol of participation in the victory entered the performative action en masse. Year after year, in anticipation of May 9, people attach orange-and-black ribbons to clothing items and their vehicles. Another innovation in the victory celebration was the “Immortal Regiment” campaign, which began in 2012 as an autonomous act of commemoration for the relatives of those who died in the Second World War, but, just a couple of years later, the Kremlin completely appropriated it. The Charter of the “Regiment” forms the universal rules for the procession, which “unites people” according to the scheme of “one country—one regiment” with the ultimate goal of “turning the Immortal Regiment into a nationwide tradition of celebrating Victory Day on May 9” and “preserving a personal memory of the Great Patriotic War’s generation in every family.” In 2015, the Immortal Regiment of Russia, which became a clone of the peoples’ regiment, was de facto registered by the state. The performative procession, in which past generations merged with the very “future ones” for whom they gave their lives, has become another way to strengthen the myth of Russia’s great power and the continuity of generations.

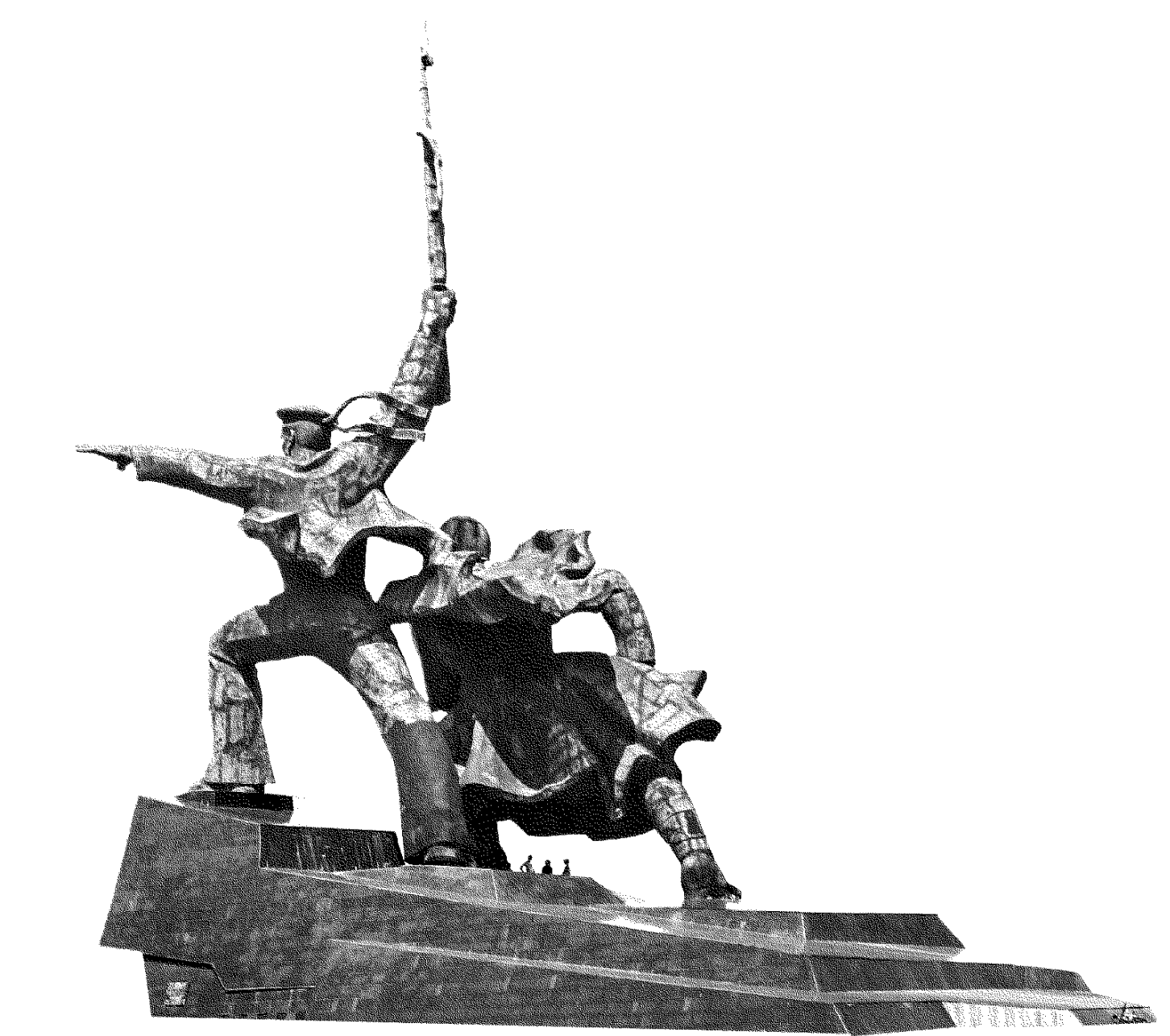

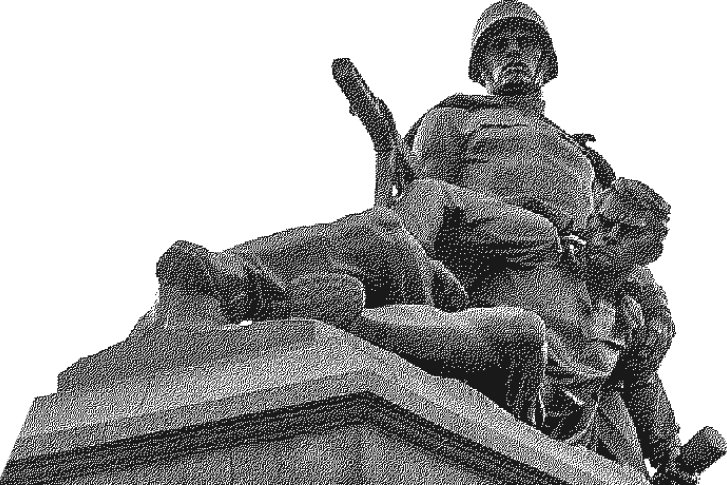

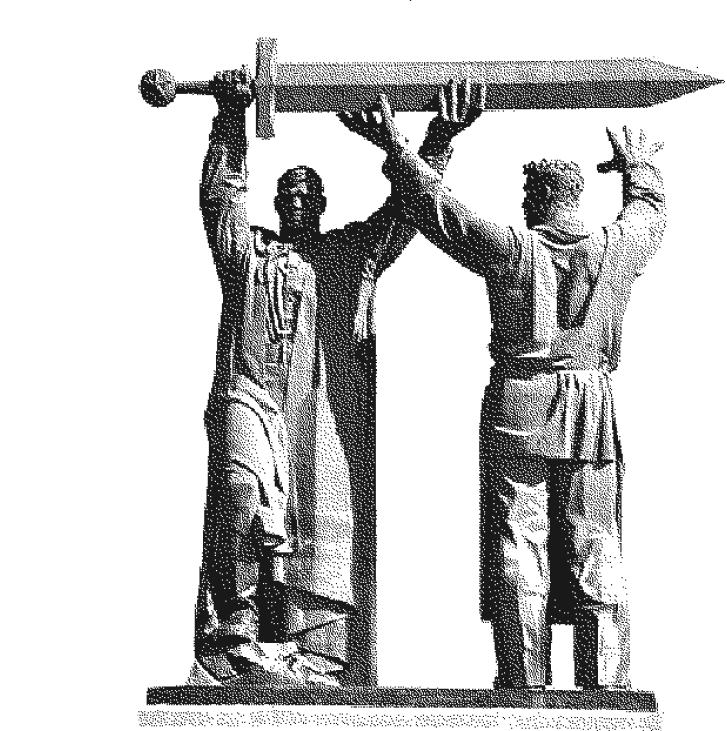

Сommemoration of fallen soldiers in the form of memorials and monuments has been—and still is—one of the main tools for reinforcing myths outside of calendar days. In this scenario, the dead are the guardians of national values and role models that give meaning to the lives of the survivors. The commemoration of fallen soldiers modifies (shifts into the future) the attitude towards death and time.

In 2017, Putin took a series of measures to develop humanitarian cooperation with foreign countries to promote “objective historical and up-to-date information about Russia” and its role in the victory over Nazism. Russian and Soviet military burials and memorial sites were given a special role. Abroad, certification of objects was prescribed, as well as their maintenance in proper condition; inside Russia, it was planned to install new memorials, monuments, and commemorative signs dedicated to the victory. In 2020 two constructions were completed: a 25-meter memorial to a Soviet soldier near Rzhev and the Main Cathedral of the Russian Armed Forces, dedicated to the 75th anniversary of the victory in the Second World War, glorifying the “greatest victory of life over death.”

In every populated area in Russia, regardless of the number of inhabitants, there are memorials, monuments, or steles dedicated to the Second World War. Often they are located in central squares or iconic places. In the village where I was born, there was a stele with the inscription “No one is forgotten—nothing is forgotten.” Every day on my way to school, I passed by it. My mother told me that the stele stands “in honor of the heroes who gave their lives for their homeland and your and my future, for the whole world’s future; this is a memory of them, they are alive in our hearts.” When I was a child, these words evoked sacred awe. They meant that the past and the future are inseparable and connected by blood, that I exist only thanks to those who died for me, and that if the situation repeats, I need to be ready to sacrifice my life for the state and future generations. Every year, a month before Victory Day, regardless of age, we read literary works related to the war and learned military songs and poems. As I read this kind of poetry in front of an audience, I closed my eyes, imagining myself in the place of those who fought in order to feel that I was dying or, on the contrary, surviving and saving my comrades. My voice was always trembling because of my emotions, and after I finished the reading, I ran out of the hall so that no one could notice my tears. I was ready to give my life for my homeland, I was ready to go to war, and I wanted to be like those who died in the Second World War.

Public commemoration in the form of memorials and monuments; the aggressive patriotic upbringing of children and adolescents over the past 22 years; the cult of the power of the state; the cult of victory, in which Russia is presented as the liberator of the world and Europe, and the previous generations who died for their homeland are perceived as immortal: these are the factors that formed a war-oriented Russian identity.

Conclusion

In January 1997, Rossiyskaya Gazeta awarded half of the promised money to Gury Sudakov for his article on the national idea for Russia. Sudakov proposed “six principles of Russianness” in which he juxtaposed the “Russian man” to the West:

“Personal gain is not enough for the Russian. He is eager to be responsible for the Fatherland < … > We cannot live without children and relatives, and we cannot live without our collective. Collectivism is our national feature < … > The concern of the Russian is how to tune the soul. Patience, abstinence, and self-sacrifice for others and the good—are the moral values of Russians. Through suffering, the soul grows stronger, and human abilities are being realized < … > Conscience and truth are the God of Russians, and repentance is an obligatory principle of being. Morality is the core of any civilization, but, it seems, it is especially true for Russian civilization < … > Society, Motherland, glory, and power are more significant for a Russian. Efficiency is less developed in our country—that is why we realize our patriotism through sacrifice and charity.”

This single award-winning article only describes the “Russian person,” excluding other nationalities of Russia from the field. The newspaper has also published other passages, which ranged from the need for penance for the past to the need for the return of the empire. Having highlighted Sudakov’s text, the editors never published the winner. In the spring of 1997, the competition was terminated, followed by the explanation that what mattered the most was the process of finding the idea itself, not the final result. Yeltsin’s government’s struggle to form a new national myth has failed. Yeltsin resigned from his position without succeeding in building symbols and traditions around positive memories of the founding of Russia and the adoption of a new Constitution.

The victorious nationalist idea shaped a society where paramilitary courage and patriotism became popular culture. War has become not just the norm but a sacred event that part of society eagerly yearned to repeat.

One can only speculate about the changes that must happen so that this national idea can cease to exist. But if for a second we imagine that the myths built on the Second World War are no longer relevant, what kind of state idea can Russia have then? It appears that the only possible mythology for Russia (regardless of whether it retains territories or falls apart) should be the anti-national one, which is developing according to the formula “no memory, no identity; no identity, no nation.”