Editorial note

After the publication of the text we received a critical commentary on the absence of information on Karakalpakstan, or Qaraqalpaqstan land, people, struggle and activism related to the Aral Sea desertification. As it is a fair and very much needed critique, we decided to make this note and address the issue.

Qaraqalpaqstan is an autonomous republic of O’zbekiston with the capital in No’kis (Nukus). Being situated in the north-west of O’zbekiston, in the lower reaches of the Amu Darya river and on the former southern shore of the Aral Sea, Qaraqalpaqstan have been the first and the most affected by the ecological catastrophe of the water body’s desertification, as our readers fairly highlighted.

The Qaraqalpaqs are an ethnically diverse Turkic-speaking people, who make up, according to different data sources, 30 to 50% of the inhabitants of Qaraqalpaqstan. Other ethnic groups living in the republic are Khivan O’zbeks, Qazaqs, and Yomut Turkmen. The regions of Qaraqalpaqstan that faced the most severe consequences of cotton production and the Aral sea shrinkage — Moynaq and Qońirat districts — are populated by Qaraqalpaq people predominantly.

“For Karakalpakstan, the Aral Sea crisis is not just about lack of water: air quality, nutrition, climate, the economy, and public services have also plunged into crisis.

Social implications have also been broad including health effects, increasing outmigration, and economic decline — the secondary impacts of which further threaten to lock the population into a downward spiral and weaken their ability to adapt and cope”, says The Doctors Without Borders report of 2003.

As the Minority rights group points out, “this [Aral sea devastation] environmental disaster has had serious economic, social and health consequences for the ethnic Karakalpak population, which is native to the region immediately around the sea. Karakalpaks have lost their traditional livelihoods and are being forced to move away from the sea to find work and healthier environmental conditions”.

Preface

As I was writing this piece, I questioned myself a lot about what the Aral Sea is for me – how I picture it and how I would describe it. To be honest, I have never visited Moynaq (also Muynak, situated in the Republic of Qaraqalpaqstan, which is an autonomous republic of O’zbekiston). My knowledge of the catastrophe preceded any understanding of the sea itself. It is hard to accept that I can never see it as it was. My initial associations with the Aral Sea will always be linked to saksovuls (Haloxylon, planted in the seabed to prevent soil erosion) and the salt left in the seabed.

About Aral Sea

The Aral Sea is known by the local Qaraqalpaqs and O’zbeks as the Aral Teńiz1. The Aral Sea is a closed basin lake situated between the republic of Qazaqstan to the north and the Republic of Qaraqalpaqstan to the south, amidst Central Asia’s vast deserts. ‘Aral’, derived from Mongolic and Turkic languages, translates to "Sea of Islands", a reference to more than 1,100 islands that dotted its water years ago2. It was known as the 4th largest lake in the world before it started shallowing dramatically.

The Aral used to provide beneficial conditions for the Qaraqalpaqstan’s population, agricultural production, and the environment. It regulated extreme weather conditions by warming the air in winter and cooling it down over the sea in summer. Additionally, the sea supported the fishing industry, providing employment opportunities for the Aral Sea coast's population and contributing to the regional economy.

The Aral Sea began to dry up in the 1960s after irrigation projects diverted the rivers that fed it in the former USSR. Over the past five decades, the area of the Aral Sea has decreased by almost 3 times, the water level has declined by 29 meters (almost 15 times its original volume), causing increased salinity and fish extinction3.

By the late 1980s, the water level had dropped to such an extent that the entire lake split into two separate parts: the northern Small Aral and the southern Great Aral.

The Starting Point of Shallowing

As a terminal basin with no outflow, the Aral Sea’s water level heavily depends on the inflow from its two major rivers – the Amu Darya and Syr Darya and net evaporation. Before the 1960s, water consumption was balanced by return flows from collector-drainage networks – systems designed to collect and manage surface and subsurface water from smaller, local drainage systems and channel it to larger, main drainage systems or disposal points. However, since the 1960s this balance has been sharply disrupted4.

The reason for this disruption was the poorly planned irrigation policy implemented by the USSR, which pursued the idea of cotton independence more aggressively than Tsarist Russia had. As a result, the shallowing of the Aral Sea was traded for the prosperity of the cotton industry. The USSR heavily depended on irrigation to expand the cotton fields in Oʻzbekiston, a region with an arid, continental climate characterized by infrequent rainfalls and high evaporation5. Excessive water usage for irrigation transformed what once was the world’s fourth-largest lake with rich flora and fauna into a desert.

It all started with the resolution “On the Further Increase in Grain Production in the Country and on the Development of Virgin and Fallow Lands” (March 2, 1954)—to use “the virgin territories” of Qazaqstan, Uzbekistan, Siberia, the Volga region, and the Urals for agriculture. This was followed by a decree of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the Council of Ministers of the USSR “On the Irrigation and Development of Virgin Lands of the Hungry Steppe in the Uzbek SSR and the Kazakh SSR to Increase Cotton Production” (August 6, 1956)6. In Uzbekistan, the area of irrigated lands grew from 1.2 million hectares in 1913 to 4.2 million hectares in 1990. This expansion was accompanied by the extensive usage of the water from the Amu Darya and Syr Darya (over 90%), primarily for the irrigation of cotton and other crops7.

By the 1950s-1960s, it was already known that a major expansion of irrigation in the Aral Sea basin would reduce the inflow to the sea and dry it up over time. Unfortunately, the experts focused solely on economic benefits and ignored inevitable environmental risks: some even proposed using the dried-up seabed for agricultural needs8. Thus the sea was seen as a worthwhile sacrifice.

By the end of 1970, the Syr Darya no longer flowed into the Aral, and by the late 80s, the same was true for the Amu Darya.

The cotton fields were increasing to fulfill industry needs, draining Aral and resulting in an imbalance between water inflow and loss. At the same time, water usage was very inefficient, irrigation was carried out without accounting, and huge losses occurred in all areas. In fact, less than 50% of the water taken from the rivers reached the fields.

Siberia to Aral

In 1968, when the Soviet Government realized the scale of the catastrophe caused by prioritizing cotton production, they proposed diverting Siberian rivers to flow into the Aral Sea. The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) Central Committee tasked the State Planning Committee, the USSR Academy of Sciences, and other organizations with developing a plan for redistributing Siberian rivers to flow into the Aral basin. However, the project never advanced beyond the design and survey phase. The project was criticized by academicians including Alexander Yanshin, a Soviet Russian geologist and later vice-president of the USSR Academy of Sciences, who was mainly concerned about the potential flooding of historical monuments in Central Russia. Writers including S. Zalygin, V. Rasputin, V. Belov, V. Astafiev, and V. Shukshin, also joined the opposition emphasizing the project’s negative environmental consequences for the population of Siberia. In 1986, the Central Committee of the CPSU and the Council of Ministers of the USSR issued a resolution “On the Cessation of Work on the Transfer of Part of the Flow of Northern and Siberian Rivers.”9

The question arises: Were there no academicians who could foresee the inevitable disaster facing the local populations near the Aral Sea, similar to the foresight they showed regarding the Siberian Rivers project? Same writers who were concerned about the ethical side? Couldn’t they have anticipated the severe and nearly irreversible impacts? Or did the government view this as an acceptable trade-off for the benefit of the cotton industry?

With the collapse of the USSR in 1991, the Aral Sea became a part of the independent states of Qazaqstan and Oʻzbekiston, bringing to an end the Soviet plan to transfer the waters of distant Siberian rivers to replenish the sea.

The cotton expansion policy developed by the USSR showed little interest in the well-being of the local population of Qaraqalpaqstan. It almost determined that the government would sacrifice natural resources in the pursuit of economic profit. The government’s drive to become cotton independent was so intense that it overlooked the risks for local communities of Qaraqalpaqstan who depended on the Aral Sea on economic and climate levels, as the Aral was the source of people’s livestock, mainly the fish industry, and provided a balanced weather on the level that affects the quality of life.

Colonized Cotton

Why was the USSR so eager to become self-sufficient in cotton production?

Before 1861, the American Civil War, the U.S. dominated the cotton market, with cotton cultivated by enslaved Black labor. The economic consequences of the American Civil War led to a “cotton famine” as the US imports of raw cotton fell by 96%10. In the late nineteenth century, Russian, Ottoman, and European manufacturers grew increasingly concerned about the rising costs and the United States' monopoly on the cotton market. As a result, they decided to exploit the resources of their colonies. The British began consuming more Indian cotton, the Ottomans expanded cotton acreage in Egypt. The French eyed Algeria for its potential, the Portuguese turned to Angola, and the Germans looked to their newly acquired colony of Togo. The Russians, in turn, shifted their focus to Central Asia, which had been incorporated into the Russian Empire in 1867 as the Governor-Generalship of Turkestan after a series of military conquests11.

During the Soviet era, cotton cultivation remained a major focus. In the 1920s, Lenin allocated substantial funds for irrigation development in southern Kazakhstan, marking the beginning of a significant infrastructure project. This was succeeded by a five-year plan aimed at reconstructing the water systems across all cotton-growing regions in Central Asia12.

Embedded Cotton Culture

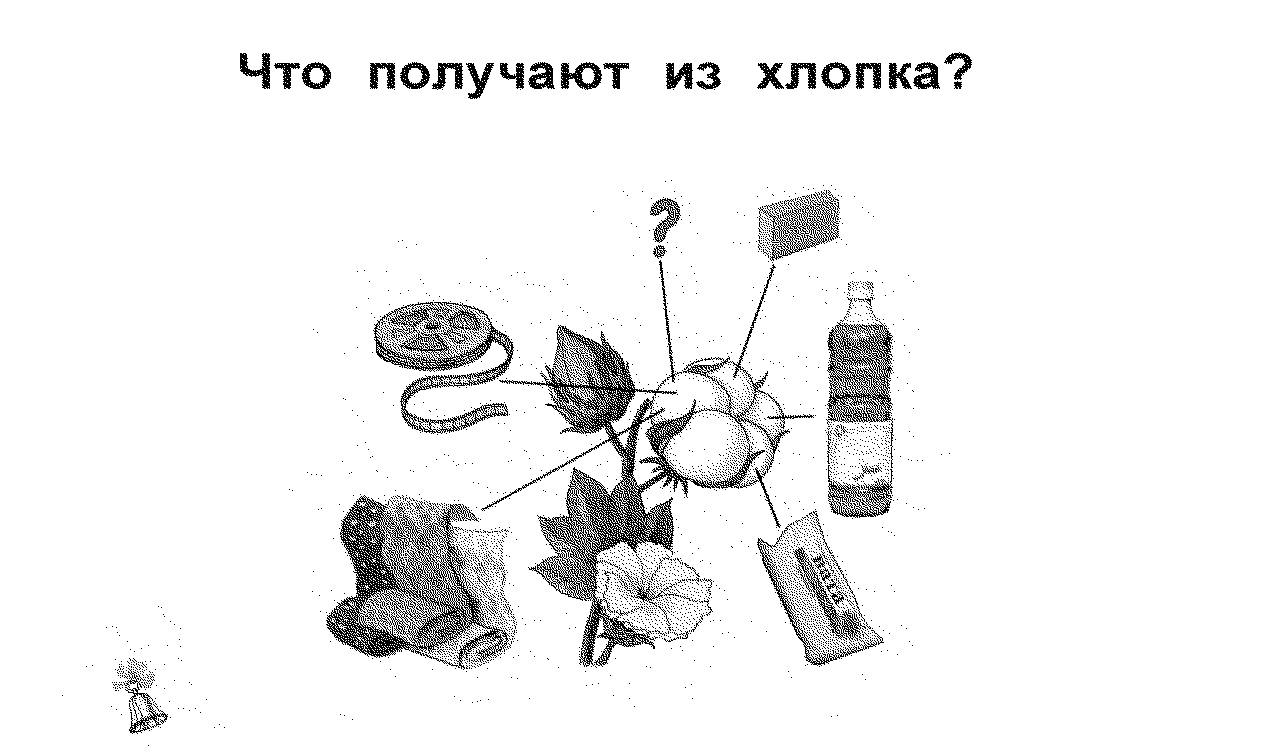

In Oʻzbekiston, the representation of cotton is deeply embedded in daily life. Cotton motifs appear everywhere—from building facades to household dishes. Its presence is so pervasive that it often goes unnoticed by locals. Cotton features in clothing, advertisements, films, and songs, becoming inseparable from Oʻzbek identity. Cotton seems to have seamlessly woven into the fabric of daily life, accepted as a natural part of the culture.

Was it always the case though? Its symbolic prominence grew during the Soviet years, when cotton became ‘viral’ and was depicted in various forms of art. The most prominent of them is the “Pakhtagul” which is the most known ornament used on dishes, becoming a staple in every Uzbek house.

As the academician and artist Tursunali Kuziev states: “A mature cotton ball of perfect shape is practically absent in the pre-Soviet imagery. Ancient and medieval wall paintings, majolica, tiles, and mosaics contained images of flowers and petals of lemon or pink flowers. Even the Islamic “Islimi” ornaments created by the craftsmen of Movarounnahr are replete with stylized cotton flower patterns.”13

The establishment of Uzbekistan's main football team, Pakhtakor (meaning “cotton picker”), in 1956, coincided with the USSR’s heavy focus on cotton production. Additionally, the deliberate effort to embed cotton as a central symbol in Oʻzbek identity manifests with the construction of the Pakhtakor subway station, designed with cotton-themed motifs. These examples prove how deeply the Soviet government sought to integrate cotton into the national narratives, and strengthen its association with Uzbekistan.

From my personal experience, I can say that it was a well-planned campaign: growing up, I have built strong associations between O'zbekiston and cotton.

I got acquainted with cotton when my parents would leave for the fields during the cotton picking season, sometimes for a weekend or even a month. My mother recalls waking up before sunrise, when it was still cold, having breakfast, taking her “etak” (a piece of cloth for collecting picked cotton), and heading to the fields. She would not come home from the field for forty days during her university years.

I started understanding it better when I started recognizing letters in the first grade. It was then that I got the idea of cotton as our “white gold”, a valuable resource that our country highly prized. Cotton was everywhere, and the tradition of cotton picking seemed so ingrained in our culture that its origins seemed lost in time.

After learning to read, I read poems that praised cotton in my first-grader book, emphasizing its significance as the source of many everyday items. There were also illustrations of people happily picking cotton. However, it seems that modern books for first graders have shifted away from this focus, and cotton is no longer commonly mentioned if at all.

Almost everyone I know, from my parents to my relatives, used to leave to pick cotton in the fields during autumn. I used to romanticize this and would often ask my parents to take me with them. They always would tell me that it was no place for fun, explaining that everyone would be working hard and I would just get bored.

Now I understand that there is nothing joyful in being forced to do unpaid labor.

Consequences

Suffering from the direct exposure of the Aral Sea disaster are the residents of the Aral Sea region – Moynaq. Since the 1960s, there have been reported increasing rates of eye and respiratory diseases, anemia, diabetes, respiratory illnesses, and oncological diseases14. Also as the water quality gets worse, kidney stone diseases have become more common. It doesn’t end here – the region is experiencing exceptionally high levels of infant mortality and illnesses. These health problems are directly linked to the sea’s recession and environmental pollution caused by the heavy use of toxic chemicals in irrigated agriculture, particularly during the Soviet era. The cost of those soviet policies is not only paid by the local population of Qaraqalpaqstan. The animals are also victims as their natural habitat was reshaped and filled by hazards, turning the area once rich with biodiversity into a desert — Aralqum.

Dust storm peaks originating from drained sea beds are a great threat. These storms carry salt deposits contaminated by the vast majority of pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizers used in cotton irrigation by principle the more the better. Dust storms increase their reach year by year – to the point that the contaminated salts from Qaraqalpaqstan have been detected in the blood of penguins in Antarctica, on the glaciers of Greenland, in forests in Norway, fields in Belarus, and elsewhere15 bringing the problem to the global level.

The most dangerous aftermath of the crisis is the potential transformation of Vozrozhdeniya Island16 located in the Aral Sea into a peninsula. Ironically named ‘Rebirth’ in Russian, this island was once a site for deadly disease studies (Siberian plague, bubonic plague, brucellosis, and tularemia) and a testing ground for the Soviet Union’s super-secret biological weapons program. The program took part in the enclosed city Aralsk -7 and involved field trials, in which test animals were exposed to biological weapons samples, – through aerial dusting, laboratory tests, and decontaminating the site. In the 1990s, the program was put on halt and the city and enterprise were closed. Though hazardous materials were buried, not all of them were fully neutralized; spores of the Siberian plague are still found in the soil, especially where test animals were buried17.

Furthermore, the disappearance of the sea affected the quality of life of the population of Qaraqalpaqstan whose income and well-being were directly and indirectly linked to the Aral, which is largely overlooked. Historically, the Aral Sea played a significant role in the region, supporting key sectors like fishing and agriculture and moreover played a significant role in cultural formation of nomadic qaraqalpaqs who have been inhabitants of the region since early 18th century. It was once one of the world's richest fishing grounds, with an annual catch of 30-35 thousand tons. Over 80% of the Aral Sea coast's population relied on fishing and fish processing for their livelihoods18. Additionally, the Amu Darya and Syr Darya river deltas' fertile lands and productive pastures provided employment for over 100 thousand people of Qaraqalpaqstan in livestock, poultry farming, and crop cultivation.

Can We Bring the Aral Back?

There is much less media attention on preserving and restoring the water balance of the Aral Sea19. Instead, current discussions about water balance in Central Asia mainly focus on hydropower in the upper parts of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers, and irrigation in their lower parts. Topics include charging for water, using drip irrigation, building water regulators along rivers, and addressing the shrinking mountain glaciers.

However, hope is not entirely lost, thanks to initiatives like Qazaqstan’s Kok-Aral Dam20 in the North Aral Sea. This project can serve as an example of a successful policy, which effectively raised water levels and improved local ecosystems, leading to the return of various fish species and bringing back local communities.

In a recent interview21, Qaraqalpaq environmental researcher Yusup Kamalov stated that part of the Aral can be revived: “The Delta needs to be restored, people live there. Saving water will give us such opportunities”. He emphasized that the crucial aspect of this effort involves forest restoration and the development of a cotton variety that consumes less water: “...the forest and the river are a symbiosis, they are mutual assistance. The larger the forest along the river, the more water there is in the river. And vice versa, the more water in the river, the larger the forest. Floods moisten tree roots and forests grow better. The Amudarya tugai were exactly the same, but the forests were cut down, and, of course, the water is decreasing…”

Oʻzbekiston faces critical water management challenges due to outdated irrigation practices. Historically, ancient methods used winding channels to follow natural waterproof layers for efficient water conservation. However, since the 1920s, straight-line canals have replaced these traditional methods, leading to significant water loss as water filters into the ground before reaching agricultural fields.

This inefficiency is widespread, affecting extensive networks of irrigation channels and reservoirs. In these reservoirs, at least 40% of water is lost annually, with additional losses from evaporation. Up to 90% of water can be wasted through inefficient irrigation, evaporation, and filtration.

Yusup Kamalov explains that it is essential to modernize water management practices. Applying concrete or protective layers to irrigation channels and reservoirs could significantly reduce water loss.

Right now, there is a major effort to stop salt and dust from moving around and to keep the sand in place by planting saxauls. A similar initiative called “My Garden in Aral”22 is launched in O'zbekiston, allowing anyone to donate money to plant trees.

Postface

This is a vivid example of how indigenous people and all forms of life suffer from imperial policies focused only on economic prosperity, without properly weighing the environmental risks and human costs. The harsh truth is that people and animals who lost their natural habitat suffer, and nature suffers, while those in power count its profits. The depletion of the Aral Sea serves as an example of how empires over-exploit the resources of the colonized until they literally dry up the sea.